Just over a year since Singapore announced an overhaul of its decades-long approach in dividing housing estates into mature and non-mature towns, the Housing and Development Board (HDB) launched the first batch of flats under the new Standard, Plus and Prime classification.

Will buyers be drawn to the 312-unit Crawford Heights Prime project in Kallang-Whampoa, given its “superior locational attributes”, new open-concept “White Flat” layout, close proximity to the MRT station and the city centre, or opt for one of the seven Plus projects in “choicer” locations, with good connectivity and surrounding amenities. Or perhaps they’d choose from the seven Standard projects, which form the largest category of Build-to-Order (BTO) flats at 4,988 units.

In all, HDB is offering a bumper crop of 8,573 flats in nine towns in the October BTO launch. The BTO flats are distributed across 15 projects, which is by far the largest in a single sales exercise since the BTO system was introduced. For the first time, singles will be allowed to apply for two-room Flexi flats in all locations across Singapore. Previously, they were only allowed to apply for two-room Flexi flats in non-mature estates.

Prospective buyers have a lot to think about. A lot of that will depend on their priorities, long-term plans and personal circumstances.

Are they willing to pay more to stay near the city, or in a well-connected location? The Prime and Plus flats come with a 10-year minimum occupation period (MOP), double the typical five years, so prospective buyers will need to take into consideration the possibility of things such as divorce or changes in family size. There are also rental prohibitions, tighter resale restrictions and a 6 to 9 per cent subsidy clawback to consider.

Buyers who face cost constraints or value flexibility may lean toward Standard flats, which have fewer restrictions.

Housing accessibility for the masses

Public housing is sold at concessionary prices to ensure that housing is affordable to the masses. Buyers’ flat choices vary not just by the type of unit but also by location.

In the old town-based framework, mature towns were in areas that were more built-up and had high demand, but they faced limitations in available land for new public housing developments. Meanwhile, non-mature estates were in relatively newer towns with more land for future public housing demand.

There were 15 mature towns and 12 non-mature towns. Over time, as some non-mature towns became more developed, they became more densely built up. As of 2023, non-mature towns housed a larger stock of 593,554 dwelling units, compared with 523,843 units in mature towns.

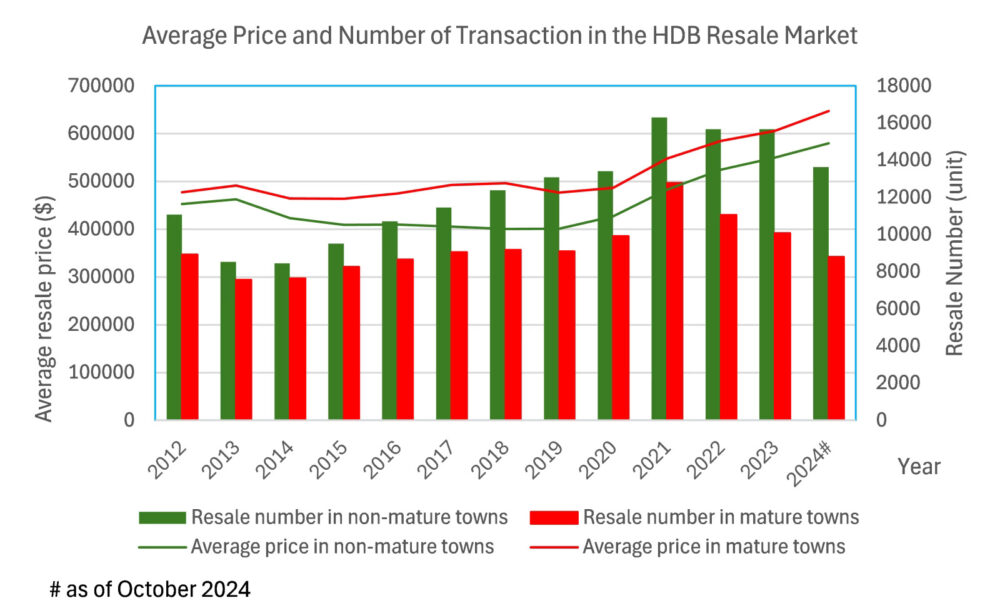

Non-mature towns also accounted for a larger volume of resale transactions compared to mature towns, although average resale prices in those locations tended to trend behind those in the mature estates.

In 2024, for example, the average resale price (based on records up to October) is estimated at S$580,124 in non-mature towns and S$647,766 in mature towns, which shows a wedge of S$67,642.

Resale transactions in mature towns were not just more expensive. More million-dollar flats were sold in mature towns, though those flats were concentrated in a few estates. The largest number of million-dollar flats were found in the Central Area. Other mature towns with a high number of million-dollar resale transactions include Ang Mo Kio, Bishan, Bukit Merah, Kallang/Whampoa, Queenstown and Toa Payoh.

The pricing of BTO flats is closely dependent on transactions in the resale markets. If the government provides the same subsidies to new Plus and Prime flats as to Standard flats, low- and medium-income households would likely be priced out of flats in those choice locations.

If left to the open market forces, some families would find it hard to afford flats in those locations. New Plus and Prime flats would only be afforded by a small quantile of eligible high-income families. Income segregation, if aggravated in selected neighbourhoods, could consequentially create tension in society.

Therefore, intervention by the government through the new classification framework was necessary to better differentiate flats between and within towns.

HDB strategies in supplying housing across towns need to ensure not just affordability but also accessibility to public housing, including choices of new BTO flats in mature towns.

Based on the October BTO launch, the distribution of the new Standard, Plus, and Prime flats of 58 per cent, 38 per cent, and 4 per cent reflect the broad compositions of flat supply in the longer term.

This will allow HDB to recognise variations between and within towns and also allocate resources to supply enough Prime and Plus flats in more expensive locations to meet the demand.

Average-income families will not need to pay north of a million dollars to buy resale flats and live in downtown and choice locations, and can consider Plus and Prime BTO flats that are more heavily subsidised. This new policy helps foster a less segregated and more inclusive society.

Moreover, first-timer families with an average household income below S$9,000 per month will be entitled to the Enhanced CPF Housing Grant (EHG), which has just been raised up to S$120,000, which will further ease their financial constraints when considering Plus and Prime BTO flats.

Mitigating the “lottery” effect

With more subsidies, Plus and Prime BTO flats will come with tighter resale restrictions.

Owners will only be able to sell those flats 10 years down the road to families with at least one Singapore citizen or singles who are Singaporeans, subject to meeting the household income ceiling criteria. For families, the income ceiling has been set at S$14,000 per month for both housing types. For singles, it is S$14,000 and S$7,000 for Plus and Prime flats, respectively.

They are not allowed to rent out whole flats after the MOP, but sub-letting of spare rooms is permitted.

These restrictions are meant to curb the speculative behaviours of buyers who do not intend to live in these choice flats but merely use them to reap a windfall in the resale market. Frequent flipping activities by a few opportunistic buyers who treat the subsidised public housing as “lotteries”, if not curbed, could destabilise housing prices, driving irrational exuberance.

The HDB’s homeownership programme has effectively enabled nine in 10 Singaporeans to own a public housing flat, which is an achievement enviable to many countries that still struggle to find solutions to meet the housing needs of a small segment of lower-income families in their societies.

The new HDB classification framework as a social enabler could make Singapore’s society more inclusive and equitable by making different housing options accessible to the masses and also improving the quality of life of these families.

The article was first published in CNA.