A day after environmentalist Jane Goodall spoke to a full house at NUS, a friend asked me: “How is the environmental movement going to survive in a post-Jane Goodall, post-David Attenborough world?”

Both are eloquent communicators about the state of environment and wildlife, and both communicate with credibility, having studied the environment for decades and sharing their experiences in a way that conveys the wonder and joy of nature. Yet both are also in their 80s.

Goodall began her lecture with a story about her mother. Four-year-old Jane had wandered into a henhouse and waited for hours, curious to see a hen lay an egg, while the police, her parents and friends were all anxiously looking for her. Instead of scolding Jane when she finally emerged, her mother patiently listened to her excited account of how a hen lays an egg.

Told in her warm and calming voice, Goodall’s story spoke volumes about the importance of parents in nurturing their children’s interest in nature.

In this climate crisis, the role of protecting and safeguarding the environment, or of addressing environmental problems, falls to every single leader, regardless of where they work and live.

But in a time of escalating environmental destruction, biodiversity loss and climate crisis, is gentle storytelling enough? In contrast to the gentle voice of Goodall, the voice of 16-year-old activist Greta Thunberg brims with anger and outrage. The global social movement she has sparked indicates that many feel the same.

Should environmentally concerned people go back to the days of mostly angry confrontations, with activists distancing themselves from the mainstream and haranguing others in an accusatory manner?

Pressing challenges

As long as the environment or environmentalists are viewed as separate and distinct from other spheres of human endeavor, we will not make much progress in addressing some of the most pressing environmental challenges. Instead, environmentally concerned citizens should strive to make the environment a part of and not apart from any human activity.

We need to take what I call an “environment-plus” approach.

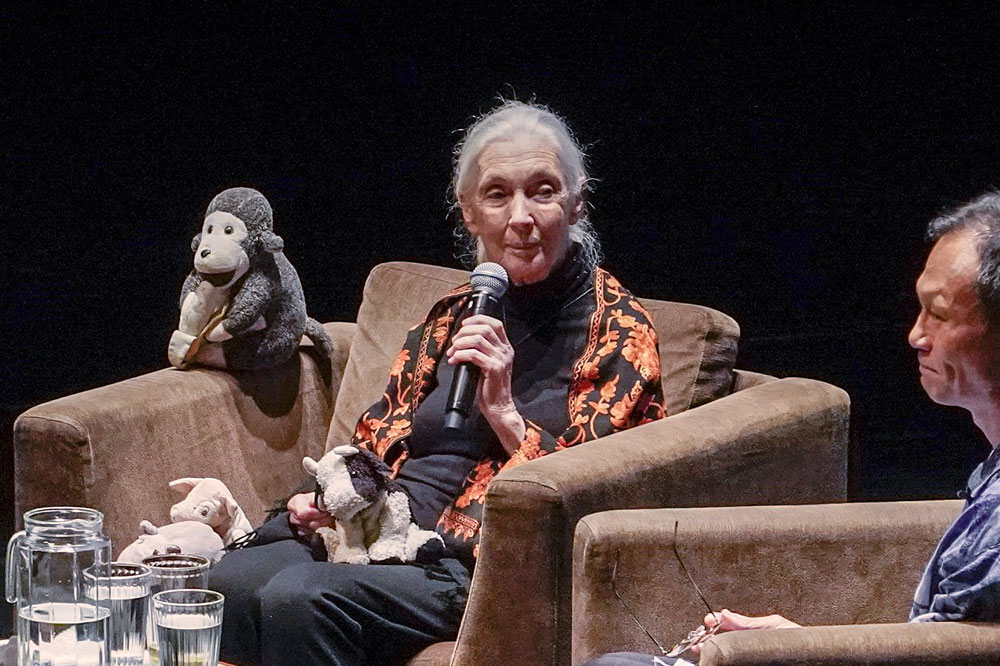

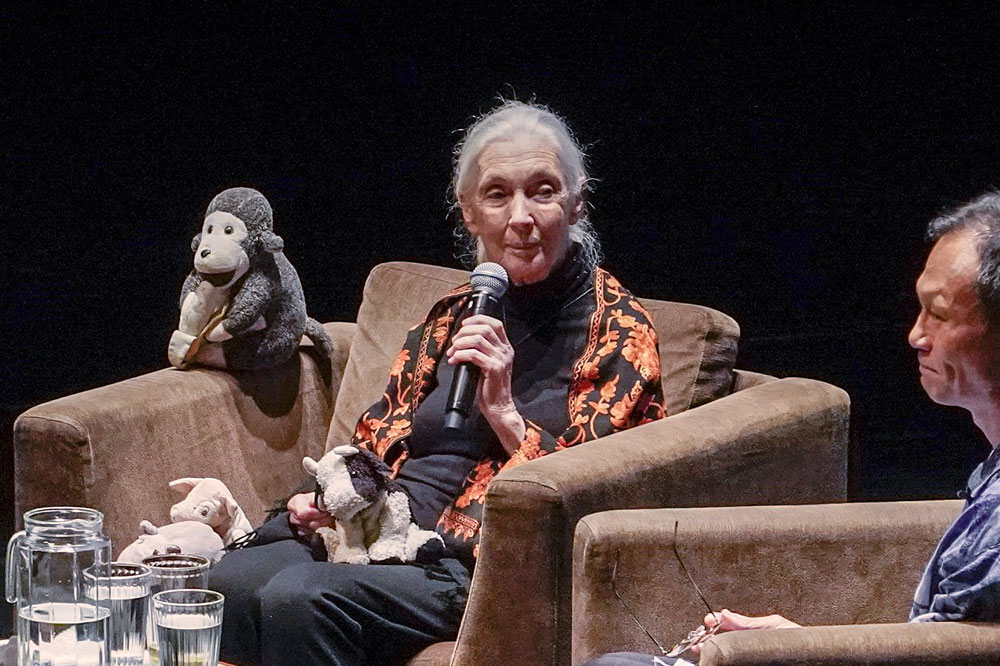

Conservationist Jane Goodall speaking at NUS

In this climate crisis, the role of protecting and safeguarding the environment, or of addressing environmental problems, falls to every single leader, regardless of where they work and live. Several have risen to the occasion.

The New Zealand government has declared that it will use the environment as a lens for making all decisions. The Italian government has decided that environmental education and knowledge of the Sustainable Development Goals will be part of every student’s education – a core element of the curriculum like mathematics or language.

Businesses in the B-Corp movement have pledged to measure both their financial performance alongside social and environmental performance. The Stock Exchange of Singapore has made board members responsible for environmental and social performance and governance.

Pope Francis leader of the world’s 1.3 billion Catholics, has issued the Laudato Si, lamenting environmental degradation, and calling on all people of the world to take “swift and unified global action” to care for our common home.

Finally, the venerable medical journal the Lancet recently launched a new journal, Lancet Planetary Health, dedicated to “the health of human civilisation and the state of the natural systems on which it depends”.

What do all these have in common? First, they are a form of leadership that clearly signals placing a priority on the environment.

Justice and ethics

Second, all these actions reflect the “environment-plus” model, embedding the environment into their areas of specialisation, decisions and everyday work and life.

Third, their actions ensure that whether at individual, organisational or societal levels, the environment becomes a default consideration in whatever decision or choice that is made.

“Environment-plus” thinking should not happen by chance. Educational institutions have a responsibility to inculcate it. The complexity and multi-faceted nature of environmental problems also means that they cannot be viewed with just a single lens. There are questions of justice and ethics.

In any environmental crisis, whether natural disasters like typhoons or man-made ones like the haze, the vulnerable elderly, young children and the poor are hardest hit. There are numerous questions about how we can we do better.

How can businesses and countries continue to prosper while minimizing environmental impact? How can we design and engineer our cities to be both environmental and healthy?

Beyond this, there is the big question of sustainable development. How do we, in the words of the Brundtland Report, meet “the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs/?“

The MSc Environmental Management Programme at National University of Singapore is one of a handful in the world that is a multi-disciplinary, environment-plus programme that seeks to help address these questions.

It is a collaboration by nine faculties and schools spanning Arts & Social Sciences, Science, Engineering, Law, Business, Public Health, Medicine, Public Policy and Design & Environment. Graduates of the programme are leaders who apply multi-disciplinary perspectives to environmental problems and work effectively with different stakeholders.

In response to my friend, I would say the environmental movement should promote “environment-plus” thinking. Instead of distancing itself from others, it should collaborate and create the belief that everyone, whatever their occupation, sector of work or stage of life, can be pro-environment.

Collaboration also means thinking across sectors and disciplines so that we address environmental challenges holistically.

With these changes, the environmental movement can reduce its dependence on charismatic leaders and turn everyone into environmental actors.