Typically, the topic of inflation seems distant to a class of young economic students. It was like talking about a mythical creature – maybe it exists in some remote places, maybe it’s in developing countries, but never in the United States or the rest of the developed world.

This lack of concern over inflation is partly because the American economy had enjoyed for many decades a prolonged period of relative macroeconomic stability. This period, known as the Great Moderation (from the mid-1980s to 2007), was characterised by robust economic growth, stability, and low inflation.

This led some to believe that high inflation is a problem endemic to developing countries and that economists have an unhealthy obsession with inflation. Despite the aggressive lax monetary policies from the European Central Bank, Bank of Japan, and the US Federal Reserve, inflation is nowhere to be seen.

But tides are turning. Just like how the Financial Recession of 2008-2009 brought us to a new reality, the recent spike in the US Consumer Price Index (CPI) of 7 percent in 2021, the highest increase for the past 30 years, brought us to a new reality of high inflation.

The concern is that past policies used to avoid a deep recession during the pandemic can lead to a volatile economy with high inflation. From the labour market to the housing and financial market, all are not spared.

To tame the market’s inflationary expectations, the FED announced in January 2022 that “The Committee is prepared to use its full range of tools to achieve its maximum employment and price stability goals.” It appears that this was sufficient to calm investors, for the time being.

Lesson from the past: Volcker’s costly fight against inflation

Inflation, of course, is not alien to developed countries. The Fed, led by the late Chairman Paul Volcker in the early 1980s, had recognised that the double-digit inflation rate observed in the US was a serious threat to economic growth and full employment.

By the end of the 1970s, the inflation in the US was over 11 percent and so was the associated long-term interest rate (10-year Treasury bonds). Usually, these two variables tend to move together, as the long-term interest rate reflects the market expectation on the inflation rate.

The long-term interest rate in the early 1980s was above 12 percent. The market had adjusted the expectations of high inflation from the loose monetary policy from the past.

Chairman Paul Volcker was determined to contract the money supply and credit, hoping to bring both inflation and long-term interest rate down.

Contrary to what he expected, the long-term interest rate did not lower immediately under Fed’s tight monetary policy, in fact it rose higher. By the end of 1984, the 10-year interest rate was above 14 percent—much higher than when the battle against inflation started.

Simply put, the market did not believe that Chairman Volcker’s commitment to fighting inflation was a credible one. The market acted on the premise of historical high inflation, leading to a painful economic recession from 1980-1982 in the US.

The takeaway of this painful episode is that fighting against inflation can be costly in terms of economic output if the monetary authority with (imperfect) credibility cannot manage the expectations of the market.

Are the current inflationary risks real?

Inflation and sudden unexpected inflation are harmful to the economy. If inflation turns out to be different from market expectations, it changes the effective rate of returns of assets.

The current market data on 10-year US Treasury bonds suggests that the market expects the inflation in 2021 to be temporary. The current yield is less than 2 percent, while the inflation for 2021 was 7 percent, indicating that the market is not expecting higher inflation in the future. Had the market expected that the high inflation was persistent and will linger for many years to come, the yield of these bonds would have been much higher to reflect the loss in purchasing power of the US dollar.

But market expectations may underestimate the real threat of high inflation.

The disruptions in the global supply chain may have contributed to the rise in global inflation in 2021, in which case, it will be transitory. But we cannot underestimate the role played by the aggressive fiscal stimulus and accommodating monetary policy, especially in the US, during the current pandemic.

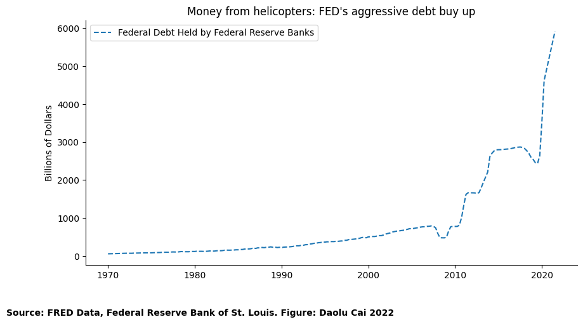

To fight the pandemic, the US federal government has issued additional debts, and most of these debts were purchased by the Federal Reserve Banks.