Interview – Inspiring Sunshine – Utopia under the Sun

“Except for the less than three hours when we stopped for meals and carried out the inspection, we have spent the rest of the day in the car. Bumpy meandering mountain roads, sodden mud tracks, broken down shacks passing for schools… and the children who came up to hug us… this is what we experienced when we visited two primary schools in in Yongan, Xishui County…”

This is what Sun Dazhao wrote on his timeline on WeChat on 14 December 2015.

Over the next few days, Sun Dazhao, a Board Member of Inspiring Sunshine Foundation (ISSF), would continue to write about his experience. He was part of the inspection team visiting schools in the poorer areas of Guizhou. This time, the tour was led by Chairman of the Board, Chen Jianguang.

The schools are in very remote mountainous areas. The team plans to visit six schools on this trip, travelling five to six hours to get to each location.

December in Guizhou is cold and wet. The temperature is about four or five degrees Celsius. They feel the chill and damp in their bones. The roads wind and wind, it rains and it snows, the roads have turned to mush, one of them faints from the arduousness of the journey.

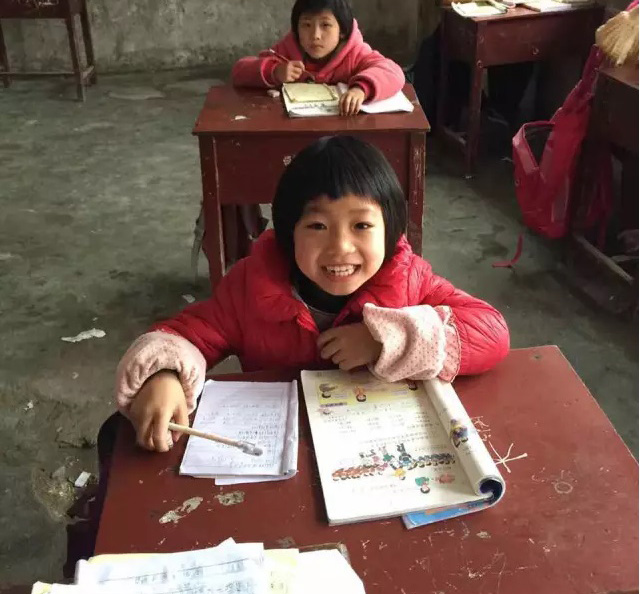

This kind of on-site inspection is necessary before ISSF undertakes to build a school. Almost every team member has undertaken such a journey of “Going Down to the Countryside”. The most common scene they will see, in these very poor regions, are “open air” classrooms exposed to the elements, tables and chairs broken beyond imagination, and the bright smiles on the children’s faces.

It’s really cold but the children are wearing very little; they are shrinking and huddling from the cold. In some schools, the children have to walk a long way, plate in hand, cheeks burnished red from the frost, to get to lunch. In some schools, they don’t even have a place to sit down and eat, or a toilet to use.

On Day Three, they arrive at Tongren and encounter a school that ticks every box under the description of “derelict” – the school had been gutted by fire, its walls are not reinforced, and it shares its canteen as the village community hall. Construction of the hostel building which begun three years ago has been halted for lack of funds and now stands, a half-built abandoned structure.

Chairman Chen loses his temper in front of the local education board, village authorities and school principal. On one hand, he is infuriated at the incompetence of the authorities; on the other hand, his heart bleeds for the children crowded into this dilapidated building, on the verge of collapse, whom he so wishes he could help.

In spite of this, the Foundation was not able to help this school. It is a common regret among the now total of 200 schools the ISSF teams have visited. Chen has seen this scenario play out over and over again, in the seven years he has been running the programme. It pains him, yet there is nothing he can do.

There is a school he visited it three years ago that haunts him to this day. The school was sited deep in the mountains in Gansu. It was difficult to get to. The team used several modes of transport—horse cart, tractor and bus— just to get there.

When the inspection team reached the school, it was already dark. The villagers, full of hope, carried torches and kerosene lamps to light their way on the dark roads. They kept company with the team the whole way, taking them to visit the school premises.

As expected, the school was in a precarious state – the roof was on the verge of collapse and there was not one good piece of boarding left. There, its solo teacher left a deep impact on Chen. He was over 50 years old and drew a salary of only 450 RMB, but for the sake of the children has served in his post for 25 years. He had looked forward to ISSF’s assistance to repair the ramshackle building for the children. ISSF was not able to do so.

“Sometimes we just can’t help them.”

As the Foundation’s Chairman, Chen is very clear – ISSF cannot throw money into a project if the fundamental issues with the authorities are not resolved. “We have to consider all aspects, to prevent wastage. Hope Project has been building schools in China for over 20 years and has received much donation, yet today, thousands of those schools are disused, or used as town halls, warehouses, pig sties or dumps.”

Building a school is not that simple

“Just donate the money and walk away, why do you ask so many questions?” Some of the local authorities and education officials will ask. They are used to seeing such philanthropy – they come, announce their generosity to some pomp and fame, donate money or resources, then leave. They take with them some touching memories, but what is left behind is still the poverty and those left behind.

But ISSF is different. Before they build a school, they insist that the local authorities and education officials show them a plan of how they intend to run the school – and it must be a pragmatic and concrete plan.

“We can’t… we can’t just build or repair a school if we are not sure if it will be supported in terms of other infrastructure and systems by the local authorities; and that it will be properly managed,” Zhang Jin says. “What is the use if there is a school building but no accessible road or even a bridge? The children will still not be able to go to school.”

Zhang Jin who has been involved in many of these projects as a Supervisor has discovered that the hardest part is not the fundraising. “Often, we have to push the authorities to walk alongside us.” At this point, Zhang Jin becomes agitated. “Some places are very keen for us to help them build a school, but their local authorities are unable to assure us of their commitment.”

Zhang Jin graduated from the Business School in 2008 with an MBA. After graduation, he returned to Shanghai where he works as a consultant. He has been involved with ISSF for over five years and has already become used to shuttling between Shanghai and Nanjing, sometimes up to several times a month. He has participated in many of the inspection tours.

He laments, “It seems we are only building a school, but there are so many things we have to consider…Every school we help requires a lot of pre-preparation work and follow up.

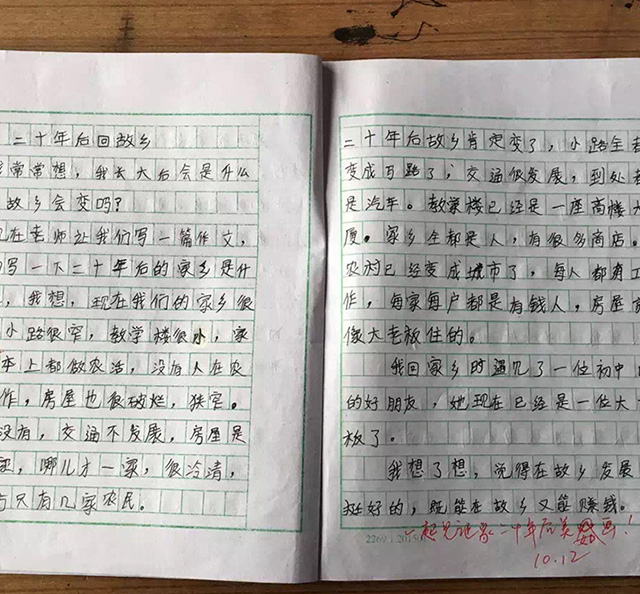

“The inspection team visits each school that applies. We talk to the principal, we assess how the teachers plan their work and mark the assignments, we visit the students at their homes and we sound out the local authorities. Only then can we truly understand the amount of support the school will receive from the authorities and the quality of the education to be provided…

“Of course, if we relax the criteria, perhaps more children will benefit. But, if we cannot get the assurance from the various departments involved, we’d rather forego the project. “We must obtain agreement and support from all other parties involved, and ensure that the project can be completed… we will not rush headlong into any project,” Zhang Ji emphasises.

What ISSF aspires to do is this: to use the three to four hundred thousand RMB in its funds to stimulate the local authorities to set up the infrastructure and systems to support the school, as well as engage the government and the local businesses to be part of the education process.

It pains him, says Sun Dazhao, to see the longing in the children’s eyes – so innocent, so hopeful. “I grew up in a village too. These kids… you give them a helping hand… that may change the course of their lives.”

However in some of these areas, the callousness and irresponsibility of the authorities preclude these for the children.

After years of observation, ISSF’s conclusion is that there are lags but the villages are not so poor they cannot afford education. Rather, the problem arises because the local authorities do not place priority on education; they’d rather place available resources into ways to increase the village’s GDP.

Some of these poorer areas even take pride in their poverty as it enables them to enjoy preferential treatment or handouts from government and provincial authorities. The proliferation of donations and assistance from other organisations have also taught them to become lazy. “With these areas, we have to just work harder – more time, more sincerity, more professionalism and more dialogue with the authorities,” says Zhang Jin.

County after county, village after village, department after department, dialogue after dialogue – ISSF have learnt to deal with all these patiently. Zhang Jin adds, “No matter how many obstacles stand in our path, as long there is some hope, we will give it a try… we have no choice, we can only try to move them with our effort, even if it were just that little bit.”

The most precious of all – How much time are you willing to give?

ISSF has a manual that runs to 240 pages – from its organisation structure, operation management, financial procedure to regulations governing construction and donation. Every little detail governing its programmes has been detailed and rigorously set down. It’s complex but these “rules of the game” is an articulation of its vision. Chen Jianguang reckons he learnt how to design and set up this type of operational systems while studying in Singapore.

He remembers a session while at EMBA class, “Professor Anthony Tseng Tsai Pen was giving a lecture on nation-building strategies. He remarked that the budget for education in Singapore is second only to its budget for national defence. This left a deep impression on me – that that is difference between China and Singapore.”

He thought long about the uneven distribution of educational resources in China, especially to the poorer areas. Because of these lags in both software and hardware, the children there are unable to break out of the poverty cycle and change their fate.

Upon graduation from NUS in 2009, and after he returned to Nanjing, he set up the Foundation. Then, he was a one-man show, with one secretary.

His mission received support from many students and classmates. One whom he remembers fondly is his classmate, Bao Hongkai. “I was just starting out with the Foundation. Bao’s business was also finding its footing, but he still supported us, and contributed to building several schools in Hunan.” Chen remembers gratefully, that these schools served as the motivation for him to continue his work to build even more schools.

Today, many of the systems of ISSF are already in place; it also has a stable team at its helm. But Chen knows, as its leader, he still has many responsibilities and there continues to be areas he still needs to be involved with personally.

He still leads inspection tours to the villages in the mountainous areas four or five times a years, with each visit lasting over a week. They are not easy journeys for him. Some of these roads are rugged and narrow, and hug treacherous cliffs. As he has a fear of heights, he cannot travel by day but waits till the sun has set before he begins his journey up the mountain. He travels through the night for several hours, and after he has finished his inspection, before dawn, he hurries back down the mountain before it gets light again.

Under his leadership and call to action, NUS Business School classmates continue to participate in this cause, some as partners on his team, others helping to manage the Fund. Sun Dazhao is one of them. While undertaking his EMBA, he heard about the work Chen, then his senior at school, was doing and in 2014, joined him. He too wanted to, in pragmatic ways, do something for the children from the poorer districts.

Sun Dazhao let us have a peek of his schedule: every month he attends ISSF working sessions; every quarter, Executive Meetings; once a year, Council sessions; and on Children’s Day, Teacher’s Day or such relevant occasions, he visits the schools. In addition, there are always new projects, organising for special teachers to visit the villages schools, summer camps, etc.

Sun Dazhao runs two business in Nanjing, as well as serves in other social capacities; but for him, ISSF sits highest on his list of priority. Like his senior, he hopes to inspire others with the work he does. For example, he encourages his daughter to collect books from her classmates to be donated to the village children; he encourages his staff to participate in ISSF projects; and even during business meetings, often talks about the work of ISSF.

“It is not about how much money you donate,” says Sun Dazhao, “What matters is how much energy you are willing to give up to help someone else at their point of need. This is the same as delivering Customer Service in any organisation, to meet someone at their point of need.”

It’s the last 100 metres that counts

For those successful in life, making a monetary donation to charity is not a difficult call. Through ISSF, Sun has discovered that it goes beyond possessing a kind heart in making a donation, and getting some claim to fame for it, and then forgetting about it.

In reality, a lot of the funds and assistance do not reach those in need.

What ISSF does is to go the last 100 metres, to ensure that what needs to be done is done, and to follow through on the detailed implementation – so that those who truly need it – teachers and students – will benefit.

For example, in some of these remote areas, the children have no books and no uniforms; they come to school in tattered clothes, to a school building that has been damaged by flood waters. Yet some of these schools have equipment for online and distance learning but they do not even have internet. The computers, white boards and projectors lie unused, collecting dust. This shows the lack of understanding of what these areas and students and teachers really need.

Chen applies a “1+N” model. “1” refers to the building of the school. “N” refers to the nth number of things that needs to be followed up on, to improve the “software”. For example, he organises for special teachers to give public lectures, and extends the invitation to all the teachers in the county; he invites psychologists to train village teachers to counsel the left-behind children; he sets up book corners so each child may have a chance to read.

Chen has a grand plan. He hopes to set up 101 schools in the poorer regions in Central and Western China within ten years. Why 101? “100 is full marks. We want to give that little bit more, to reach beyond ‘good’ to ‘excellent’.”

Since 2009, ISSF has built 61 schools. The goal is to pick up the pace and build ten schools per year, a goal and pace his team is aligned with.

Chen also hopes his schools will become a model for others. Chen and his team have noticed that many charity organisations in China have also started to focus on the left-behind children, or are organising training programmes for the village teachers, or are assisting them in setting up internet capabilities. He hopes to work together with these organisations to change the playing field for these very poor communities.

These last few years, more and more classmates from the Singapore Business School have joined him. They donate money, they put in effort. None of them receive any salary from the Fund. Sometimes they even have to recuse themselves if there are potential areas of conflict of interest.

Chen says, “For us, it matters more who we journey with – that we share the same goal and the same values, that’s what’s important.”

They have a tacit understanding – to use their management training to make the Foundation more transparent, more efficient, more responsible – and help ISSF create a Utopia for the poorer children of the country.

Report Card of ISSF as of June 2016:

Built 61 schools

Set up 40 libraries

Collected and donated over 90,000 books

Set up 238 Book Corners

Funded 74 children

Opened 4 training centres

Made 47 Inspection trips

Organised 204 training sessions

Among the 61 schools, four were set up from donations by Business School alumni and bear the NUS Business name. They are:

Hunan Province Shuangfeng County NUS Hanpo Hope Primary School

Jiangxi Province Suichuan County NUS Shatian Hope Primary School

Sichuan Province Puge County NUS Sunshine Hope Primary School

Chongqing Municipal Changning County NUS Qingshan Hope Primary School (This school was partially funded by donations from EMBA alumni , before ISSF was set up)

Aside from the abovementioned Cheng Jianguang, Bao Hongkai, Zhang Jin, Sun Dazhao, there have been many other classmates from NUS Business School that have journeyed with Inspiration Sunshine. They are Shu Zun, Li Wenjun, Chen Dawei, Han Jin, Chen Xianbao, Cheng Dongmei, Zhou Bin, Yang Zhenbu, Huang Guangwei, Xu Xiaowei, Lin Yinglu, Zhang Runbin, Yan Jun, Qin Yin, He Wenjun, Yang Hua, Ng Aik Min… their alma mater salutes them, and all the others who have contributed too!